Before Netflix drops the 2025 Berubara (produced by Japanese animation studio MAPPA) on April 30, I’ll have you know I’m a longtime fan of Riyoko Ikeda’s work. Her command of European history and culture is extraordinary, and she’s always wielded it in service of nuanced storytelling. Her four-volume manga series The Ring of the Nibelungs, entirely drawn by assistant Erika Miyamoto (yes, manga authors sometimes have assistants, just like Renaissance masters) is a case in point. Ikeda peeled back the layers of 20th century ideology and 21st century scorn to reveal the original libretto in all its force, through a careful reading that demonstrates her acquaintance with Wagner’s non-fiction, theoretical texts.

The Rose of Versailles, her best known manga (1972), deserves to be read with an eye to its complexities, which the movie will have a hard time showcasing in 113 minutes. Even though Oscar François de Jarjayes has been widely adopted as an icon of queer visibility, and her journey from the ranks of the nobility to universal humanity has been celebrated as similarly progressive, the manga tells another story. Below the surface of The Rose of Versailles, the Rights of Man and gender nonconformity are at cross purposes, and hewing to this uncomfortable realisation may reveal something more transgressive.

In fact, Berubara (ベルサイユのばら, Berusaiyu no bara) resembles nothing so much as the sentimental education of two women, the queen and the amazon, one of them raised in hyper femininity, the other forced from infancy to present as male. They start from a similarly high level of artifice (if directed to opposite ends) and slowly and painfully make their way to a sort of authenticity. That conquest of personal authenticity, though, happens from within their shouldering their roles, and by using the inauthentic means provided by society: not always consciously, but never in a way that diminishes the human value of their choices.

The fact that Oscar’s gender nonconformity was imposed rather than chosen makes a nontrivial point: growing up as a woman does not simply entail being socialised as female, but rather being so socialised to varying degrees of femininity. Each girl is feminine in her own way, depending on how her family and peers view her, and what they value in a woman: whether beauty, grace, seduction, good character, motherliness, modesty, hard work, seriousness, or something else. Some of these vary with social class, others with religious background. People responsible for raising young girls can hyper-sexualise them for clout, or encourage them to lean into tomboyishness. Oscar and Marie Antoinette are extreme cases of a universal reality.

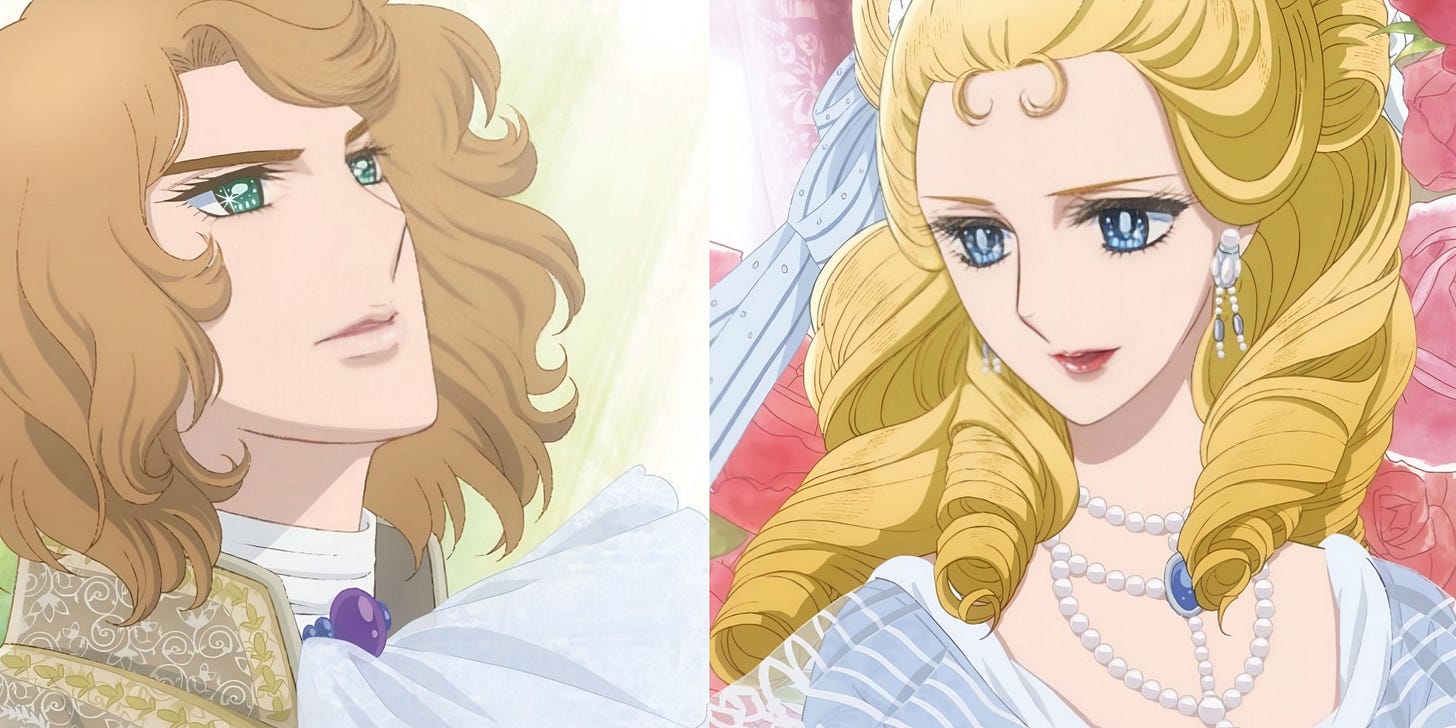

Ikeda’s Marie Antoinette is not the historical Marie Antoinette, of course, and the same is true of Swedish Count Axel Von Fersen. Lady Oscar was inspired by François Augustin Regnier de Jarjayes, but there is no reason to doubt that the latter was a man in the conventional sense of the term. I can’t write registered male at birth, because so is Oscar. It is one of the many ironies that defamiliarize our received language for such matters.

By present-day standards, Marie Antoinette inhabits a queer world where both men and women are tilted towards the feminine. This is evident not only in dress, makeup and coiffure, but also in sentiment. It is a commonplace that, for most of Europe's history, noblemen’s masculinity did not hinge on short hair or unfeeling ruggedness. (This has also given rise to the much-ridiculed academic study of masculinities in the plural, prefaced by temporal descriptors such as Early Modern.)

French peasants were much stricter in their observance of gender, mainly because their existence was bound up with the landscape and its fertility. Even though men and women shared the same agricultural labour, performed the same chores, and were adept at the same household crafts, they each had separate spaces and instruments. Agricultural tools were gendered: a man’s sickle was not the same as a woman's, either in shape, dimensions or technique. (In Romance languages, objects can be grammatically male or female.) Only a woman could enter the cellar to retrieve food. Many of these facts were tied to what we might call superstitions, but others had probably a sound basis in hygiene.

In addition to observing looser boundaries for gender conformity, clergy and nobility showed no compunction in thwarting nature to serve excellence. (Nature was not a very important part of their legitimacy anyway.) The existence of castrato singers like Farinelli makes Oscar's upbringing seem entirely believable, and rational and humane in comparison. It is in this world of androgynous beauty, elegance and esprit that Fersen and Marie Antoinette’s love story unfolds.

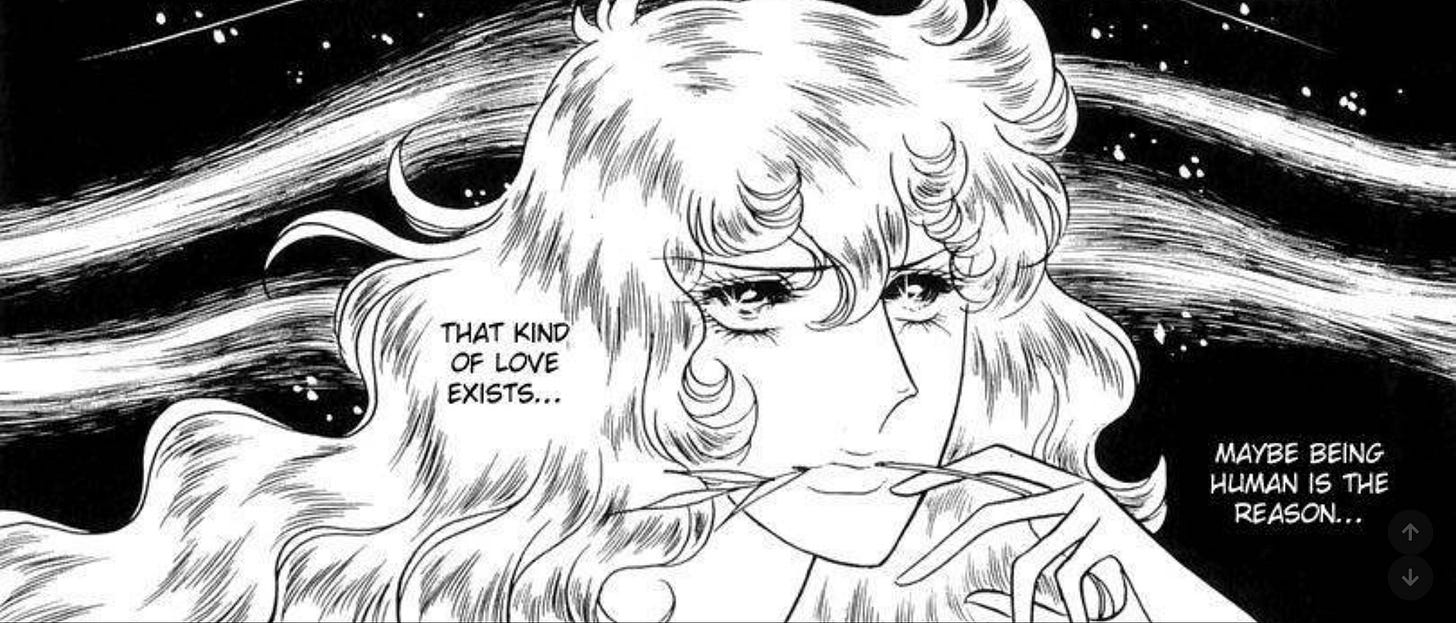

It is both an artful collaborative construction and an aristocratic duel. Nobleman and noblewoman know the canon, it's easy for them to produce a variation on the theme of love. Each completes the other's cues with suitable words and gestures, so as to compose a beautiful tragedy for four hands. Hazarding disproportionate, splendidly foolish moves, each dares the other to raise the stakes even further, in a fierce contest of loving honour. A command may be issued, hoping to inspire disobedience. (Disobedience may misread the intention behind the command.)

Marie Antoinette and Fersen are fine souls, great writers, great dramatic actors, true to the spirit of the story they are weaving (perhaps all the more worthwhile as it might have been the last of its kind, at least in France), but they are not authentic lovers as we might think of such. Or indeed, as the following century would judge. In Stendhal's classification (1822), theirs would count as mannered love or vanity-love, albeit of an extremely intense kind. It is founded on ceremonial declarations, flaunted in defiance of court and populace, and fed by leisure and luxurious settings. It is hard to see how anyone could fail to be flattered by a Queen’s attention.

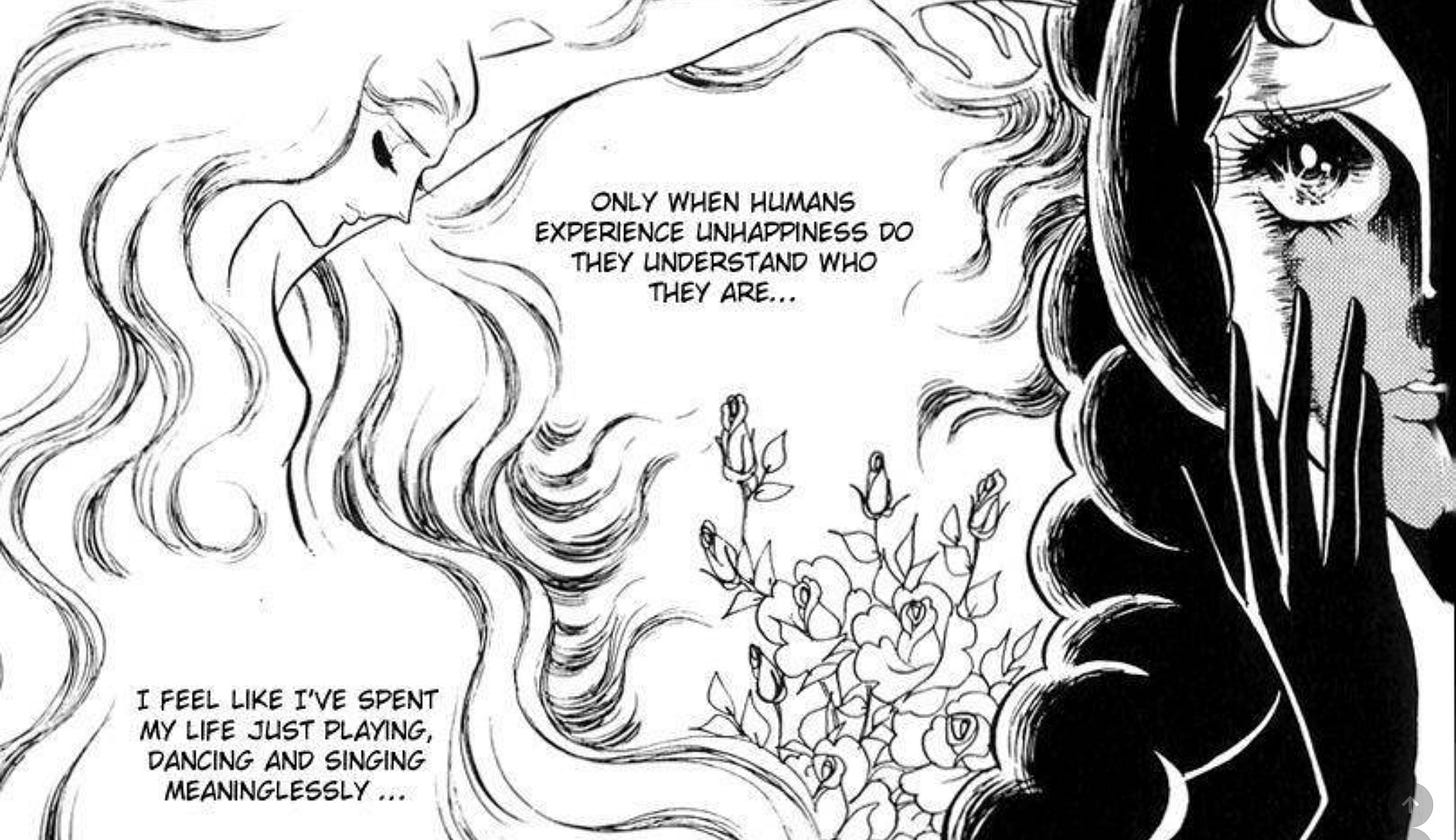

Marie Antoinette is made into a woman not by love for a man, but by sorrow. Losing her children one after the other reminds her of what is nearest to her heart. If it is true that “only when experiencing unhappiness do human beings understand who they are,” she understands she is a mother, and that what she had initially tolerated as a burden and a duty (the bearing of heirs for France) had been her tenderest happiness.

Even so, she finds strength to face her retribution in the same artificial constructs that had nourished her love for Fersen: she wants to die as a Queen, because Queens do not fear death. To her, this is sustenance. Making a place for the terrible demands of reality does not require her to immediately discard the only way of thinking she has ever known, since she has nothing to replace it with. However, she can imbue her old way of thinking and acting with the grace of newfound meaning, elevating a grand manner to new heights. She does not renounce her love for Fersen: on the contrary, she now models it after the selfless devotion she feels towards her children, exhorting him to save his life and go on living in her stead.

Fersen is also Oscar’s first (unrequited) love, or youthful infatuation. As a member of the same milieu, Oscar finds the relationship between Count and Queen intellectually irresistible: she is “in love with the idea of love”. Since she continually oscillates between regret for her denied femininity and bold embrace of her masculine identity, it can be hard to understand which person she actually loves more.

She seems to feel for Marie Antoinette what most women feel for the public persona of a man: longing for a role she is not allowed to play (in this case, the coveted role is “beautiful lady,” which, had Oscar lived a normal life, should have been hers as a matter of course.)

By contrast, she already knows Fersen’s perspective from the inside, so that element of social curiosity and attraction is missing. However, Fersen as a love object allows Oscar to imagine taking the Queen’s place. Normally, Oscar feels bound to despise and ridicule frivolous court ladies (maybe to hide her true desires, maybe not to risk being commiserated with), but she has nothing but commendable reverence for the Queen of France.

All things considered, her “immature” infatuation is a stunning shortcut, a psychological escape route that gives her an all-round acceptable way of dealing with her conflicting emotions and self-perceptions.

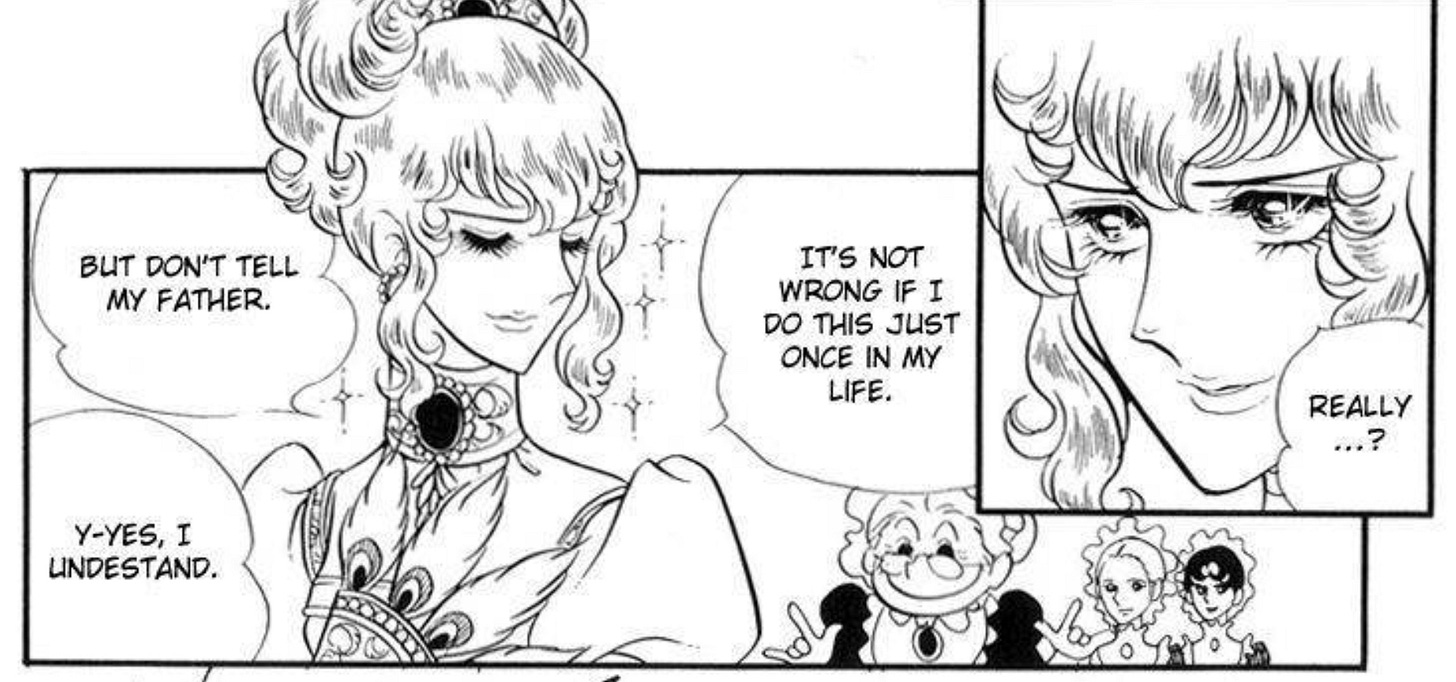

Appearing before Fersen in feminine attire once seems to satisfy her desire. Something Fersen says to the “unknown” lady (he’s recognized Oscar through her disguise) may be crucial: to him, she is a courageous, beautiful woman ready to die for her ideals. Oscar might just have needed to hear someone describe her admiringly as a real, desirable woman endowed with eminently masculine virtues. One does not annul the other. She doesn’t have to feel like she’s betrayed her essence or wasted her life.

Maybe that is why she later vows to live as a true daughter of Mars (the Greek god of war), and “give her body to swords and bullets.” Oscar’s high-sounding, mythological self-description reminds us that she’s a woman of her time (and class), and would never recognize herself in our words and concepts. At the same time, her figures of speech are just as good and useful (and silly) as any alternative might hope to be.

Oscar’s confrontation with reality begins when she puts her military career on the line for Rosalie, a girl she calls “her spring breeze.” As her loyalties shift and her position becomes untenable, Oscar resigns from the Royal Guard to join the more proletarian French Guard. With downward mobility comes a revolution in the way her performance of gender is received: while nobles coolly accepted her maleness at face value and aristocratic maidens fell in love with her, the men now under her command absolutely despise and refuse the authority of a woman. In essence, what they’re saying is you’ll never be a man. Oscar reacts with impish, boyish charm, choosing to regard the slur as a backhanded compliment: “The French Guard are the first to see the woman behind this uniform. I should be flattered!” It’s pure Lady Oscar: she owns her womanhood, and supports that with impeccably executed male bravado, complete with rakish grin.

The finer nuances are lost on the troops, so she has to batter them up a bit too, both to prove her valor and to repel their unwelcome, raucous advances.

The truth is that France was slowly becoming unsafe for queer people, and for any man or woman who did not inhabit their body in complete conformity with the Enlightenment’s blueprint of the ideal male and female human beings.

From Cromwell onwards, each violent wave of democratization has coincided with a greater or lesser “male renunciation,” a term coined by John Flugel to describe how men gave up fashion and beauty as legitimate parts of their identity, for the sake of social equality. Empire fashion, though, could be read as a parallel “female renunciation.” Light fabrics, high waistlines, minimal ornamentation and natural hair were in. Powdered wigs, heavy makeup, corsets, panniers, voluminous silks were out. Femininity was to stand for naturalness, simplicity, domesticity, and an array of virtues borrowed from classical antiquity.

Not that the Empire look required less effort to pull off. But effort was applied more to the body than to the wardrobe. Slimness, posture, proportions: all was mercilessly thrown into relief. As femininity became more body-dependent and the tools at their disposal became scarce, trans people would have had a hard time presenting as female. A fashion revolution that many women experienced as spontaneous and liberating would have spelled existential crisis for them.

The Enlightenment did not stop at fashion, but prescribed distinct roles in society for men and women. Rousseau’s groundbreaking book on child rearing and education, Émile, laid out very different paths for Émile and his future bride Sophie. He is educated to become a strong independent man, both physically and morally. Sophie is educated to become pleasing, modest, obedient and supportive. Her whole purpose is to grow into the ideal wife for Émile. Rousseau wrote: The whole education of women ought to be relative to men. He even defended all kinds of domestic abuse. On a positive note, new mothers are encouraged to breastfeed their own babies, something the aristocracy never did.

As for his personal life, Rousseau abandoned all his children.

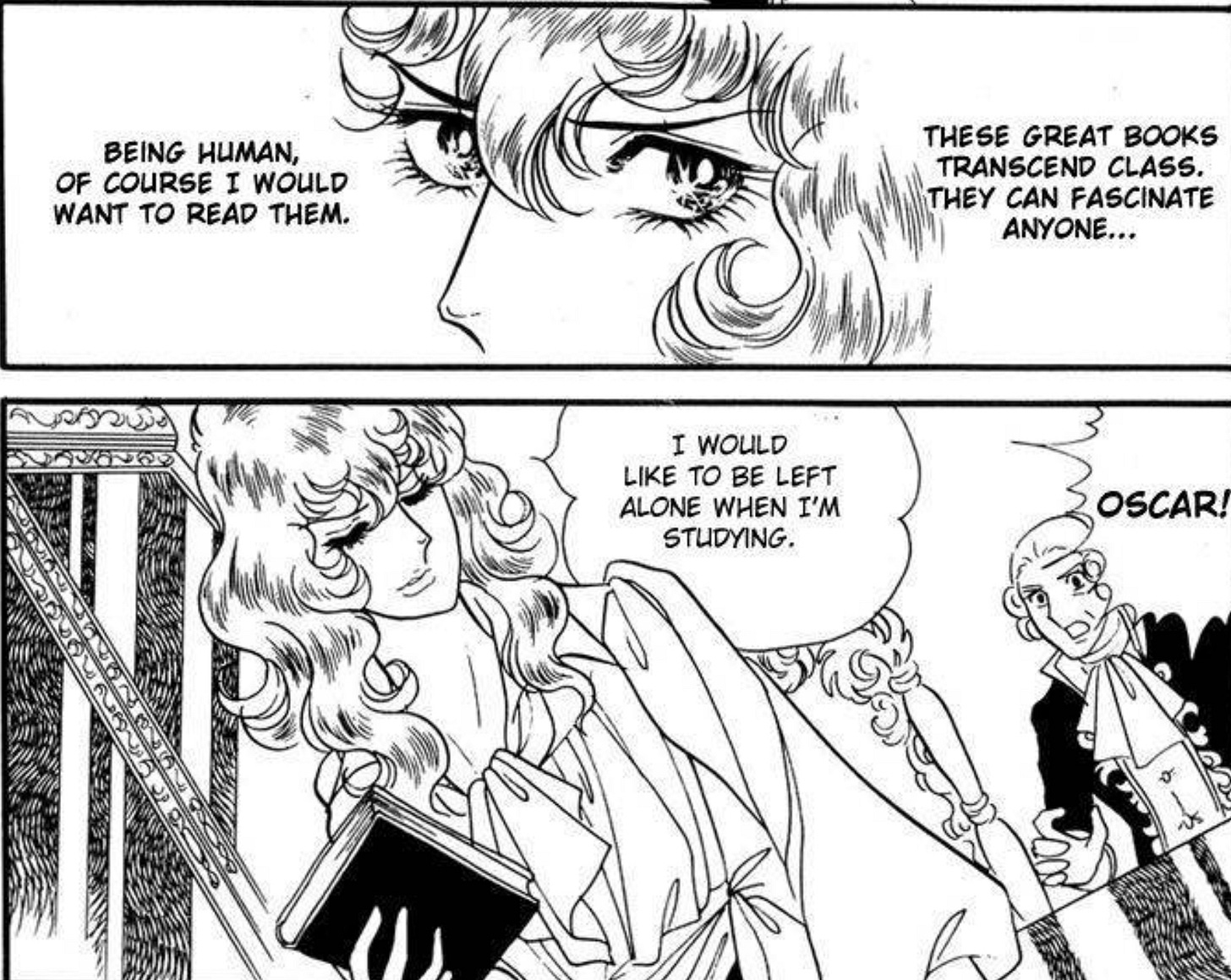

Oscar would have read every single book by Rousseau she could lay her hands on. André Grandier, her childhood companion and utterly devoted lifelong simp, is only seen reading Julie, or the New Heloise (that, he could wrap his silly little head around, full as it is of romantic notions), but it is heavily implied that Oscar, her curiosity piqued, fell down the rabbit hole. (To be fair, as a noble she might have had more reading time.)

The French Revolution was a dangerous time for a creature like Oscar, not just for its theories but also because it unleashed animalistic violence in society. In fact, the theories themselves, when closely examined, can be seen to derive their legitimacy from a return to Nature, and in ideological manipulation it remained conveniently ambiguous whether this Nature was more Rational or bestial, “red in tooth and claw”. The Marquis de Sade may have been imprisoned in the Bastille, but his credo was daily put into practice by the Terror. An English commentator, John Adolphus, dubbed Robespierre “the Tiger” and his regime a “tigrocracy”.

The Tiger, while nominally supportive of initiatives like the Women’s March on Versailles (especially in the beginning, more out of political convenience than any genuine interest in the plight of women) suppressed any attempt at an independent female take on the Revolution. The Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women was disbanded in September 1793, and the moderate Olympe de Gouges, author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, was guillotined in November.

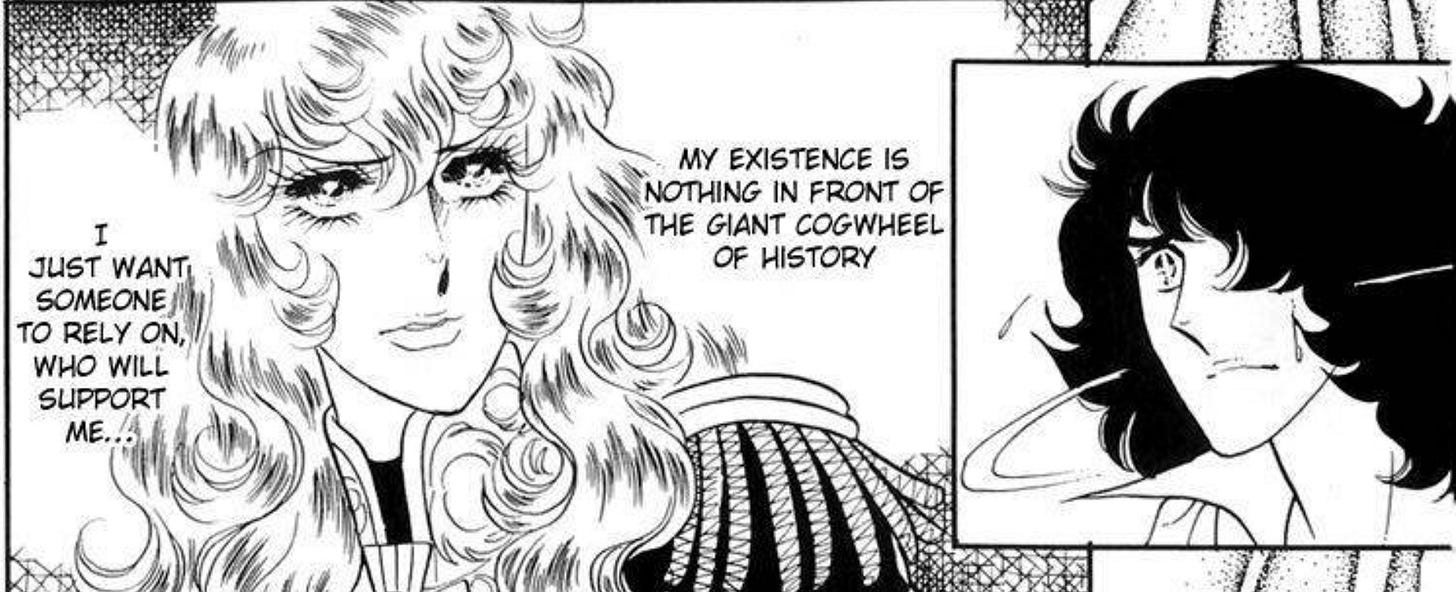

A world was taking shape in which a woman could not survive and thrive without a strong protector. Oscar’s father sees that early on, and tries to turn her thoughts to marriage. Rather than humiliate her by questioning her prowess, he makes it seem like he wants her to produce an heir. Oscar is confused and slighted, as if her father had been playing with her destiny and her feelings all her life. She makes sure the ball he throws for her is a complete failure. When her mother reveals her father's true concerns, though, she finds nothing to say, except a crestfallen “I didn’t know…”

General de Jarjayes’ actions also destabilise André, who, faced with the prospect of losing Oscar to another man, attempts both rape and murder (or double suicide by poison, but without obtaining Oscar’s consent first.) Shinjū (心中), the lovers’ double suicide, is a Japanese thing, but André is a Westerner and doesn’t tell Oscar: he wants her to go to heaven and is ready to take all the blame on himself. I don’t think this makes him look any better. Similarly, the fact that he wrests the suicide’s cup from Oscar’s hand at the last minute, or calms down and begs forgiveness after tearing off a piece of her shirt, doesn’t really make him look like a trustworthy person. I suppose some find his behaviour both exciting and endearing (he can be both! a maniac and a softie! …Ew.) To me, he's just sinister. His redeeming qualities lie in being the least ferocious brute in a world of brutes, and risking life and limb for Oscar without a second thought.

All these combined pressures and sources of aggression (Alain de Soissons and Victor Clement de Girodelle have also tried to kiss her) wear Oscar’s resistance thin. She loses faith in herself, in her ability to protect herself and her loved ones. Tired and confused, she sees her childhood with André glowing golden in her past.

It can look as if the entire male half of humanity is conspiring to drag her down. There’s something there that can’t be ignored, but it also risks stripping her of agency. Oscar has never been a victim, and she’s not turning into one now. She does fall in love with André, in her own way. It’s as if the precarious historical situation has suddenly released years of pent up energies in her.

When she proposes to André (first, it’s a bashful “I want to be André Grandier’s wife”, then it’s a battlefield “after this, we’re getting married”), she’s living something she has chosen for herself. Out of a limited set of possibilities, certainly. But is that not the case for each of us? Should we negate all real value in our lives just because we were forced to adapt to external circumstances? If we did, our quest for personal growth and self-expression would be perpetually deferred.

In her sentimental meandering through a very personal Carte de Tendre, Oscar has undertaken a journey from the 18th to the 19th century, from mannered love to Stendhalian passionate love, or Romantic love. What this means is that, even if she’s convinced she’s thrown off her noble status to embrace Humanity, she’s not really managed to liberate herself from culture. The naturalness she strives to embody is cultural, just another style of loving, the latest in a gallant pageant snaking down the centuries. Her love for André, too, was kindled by a book: Rousseau’s Nouvelle Heloise. She's just as literary as Marie Antoinette, only she doesn’t suspect it. Also, she’s entering the Romantic era with a head full of martial myths and courtly Olympian fantasies.

And yet, despite all this, before her life in a world not made for her is brutally cut short, she succeeds in becoming human in a deeper sense than the Enlightenment human. Not because of any particular action she’s taken, but out of the whole unfolding of her life. She dies as the woman Fersen had described: for her ideals. (Republican France. Freedom.) But none of this matters now. Riyoko Ikeda’s earlier words regarding Marie Antoinette might be said of Oscar: she tried her very best, and “only her God can judge her.”