If you're asked for a snarky opinion on the state of the built environment (which, like the environment at large, is assumed to be always changing for the worse), there's a response that never fails to impress: “I don’t like soulless buildings.” It's a statement we can all agree with. But do we mean the same thing? Which type of building best embodies the discursive avatar of the “soulless building”?

For most people, that avatar seems to be the concrete cube, or some other modernist visual trope like the International Style, disseminated around the globe by near-identical skyscrapers clad in glass curtain walls. “Evil” architects are routinely blamed by the public for championing this perverse style, instead of either adhering to the good example of the past, or taking a creative leap forward.

The embarrassing truth, as known to anyone who has ever pored over the technicalities of the profession, or even simply bothered to read the copy that usually pitches an architectural project to clients and peers alike, is that architects have taken several leaps forward from the heyday of the International Style to the present, and they have never stopped looking to the past. Often, these are two sides of the same endeavour.

That is not to say there are no real feuds or disagreements between architects today. But they’re framed differently, and come with different sets of insults and rivalrous implications than those monopolising most discussions online.

A strange disconnect exists between the profession and the public: not in terms of taste, (since our brains tend to be attuned to the same patterns regardless of our level of architectural literacy), but in which topics we perceive to be hot topics. The 2024 movie The Brutalist briefly gathered specialists and non-specialist around a common debate, shedding light on how unusual this situation normally is.

An example of the disconnect, taken from recent history: at some point, back when digital architecture was still a novelty, calling something a “blob” constituted a lethally funny slur. It meant that a freeform, digitally generated building was sloppy, thoughtless, wasteful and a childish eyesore to boot. The blob maker could in turn reclaim the term and own it as their signature aesthetic. You will search social media for evidence in vain: episodes of this kind are never rehearsed, and they have left almost no trace in collective memory. The public’s limited attention seems fixated on “majestic cathedral” versus “modernist monstrosity.”

Given all this, it becomes understandable why the public’s solution to the rampant ugliness they see encroaching on their space (“public” space, as it is called, with a generous helping of wishful thinking) is divided into two main camps. Either return to temples and cathedrals, or (for the more progressively minded) give us a new style. Something like Art Deco or Art Nouveau: modern, without being modernist.

But architects are not caught in an enchanted sleep that prevents them moving forward, nor are they prisoners of modernist dogma. In fact, they have resented modernism, anxiously awaiting the end of its posthumous moments. No rebellion was ever good enough for them, because it did not signal true emancipation. Only when digital architecture eased into its post-digital moment did they breathe a sigh of relief: if we are post-digital, we can’t be said to be postmodern anymore.

Let me tell you the story of how we left modernism behind.

When CAD (computer aided design) was first let onto the scene like a cat amongst the pigeons, would-be stylistic innovators willing to harness its power had a sophisticated movement to contend with. Deconstructivism (an offshoot of postmodernism) still enjoyed intellectual prestige. As a movement, it advocated maximum disjunction between parts of a building, and maximum contrast with the urban fabric in which it was placed. This was supposed to put on display the various types of difference within society, teasing out the cultural and stylistic influences within a city and making them clash in a single dramatic, eye-catching piece. It ethos was distinctly cosmopolitan.

(Critical regionalism, a movement that leveraged local building traditions and locally-sourced materials against the ubiquity of the international style, also put a premium on difference, though in a place-based way.)

For a time, the main antagonist to deconstructivism seemed to be the blob. Enthusiastically subservient to corporate branding, it sprouted big structures where fragmentation and contradiction became lost in cartoonish arbitrariness. It was the sensational, pop inversion of deconstructivism's messily participatory utopian anarchism.

Soon, though, a more formidable aspirant to the throne would emerge.

As the endlessly plastic blob finally deflated, parametric design attempted to put the house in order. Architects debated whether parametricism was a fully formed new style. As regards essence, it was characterised by a preference for curving, continuous lines and anexact but rigorous geometries. It also looked like it did have some recurring, iconic traits: it was fluid, futuristic, complex, adaptable, algorithmic. Maybe it was just a way of using new technology. But its staunchest defenders argued that parametric sensibility predated the advent of computer aided design and manufacture. There is a market based and a cultural version of this claim.

To its critics, parametricism was the crowning architectural expression of neoliberal capitalist realism, and one should have seen it coming.

Here was a design language that absorbed whatever was thrown at it, and optimised it all for efficiency. Parametricism smoothed over jagged angles, folded difference into a mixture, and meekly bowed to context. Importantly, this was not the kind of context that endures in walkable historic cities, but rather context understood as a local node in a global network of market needs. Which entailed planning buildings around access, circulation, available resources, flexibility and multiple use.

This genealogy assumes that, even before CAD made it extremely easy to plot and tweak the kind of shape that parametricism thrives on, the market had begun stimulating demand for a tamer, less obtrusive, more elegant architectural style. One that would look less obviously repressive than modernism, but would nonetheless insinuate itself, softly controlling, gently nudging and speeding the flows of people, ideas and goods.

For some, this could fit the definition of a “soulless building,” though perhaps soulless not as an inert block of stone but as a slithery siren. In its double capacity as new industry standard and emerging dominant paradigm, parametric design was destined to inherit the hate that had previously been directed against the blob and the concrete cube.

I prefer an alternative genealogy, though. One that says we were always going to try building with these sinuous lines, because architecture, being inescapably rooted in physical reality (unless it’s an augmented reality based intervention), dependent upon matter’s tolerances and possible behaviours, and the ways we learn to make sense of these phenomena, pursues its own ends regardless of styles and movements.

Architectural “populism” is right when it reminds us that buildings are not the expression of individual whim, like a painting or a sonnet, but the outcome of negotiation. This certainly includes taking stock of the forms that traditions have found over long periods of time. It includes destination, urban planning, building codes, and the architect’s public mission. We also have scientific legitimation for the belief in objectively beautiful and pleasing design, in the new interdisciplinary research field of neuroarchitecture. Even before all these, though, designing a building means grappling with physics, geometry, and mathematics.

Consider Penrose tiling. It offered a solution to the problem posed by standardised tiles, which typically induce feelings of estrangement and unease. It owes its name to the mathematician who described conditions for a pattern that varies constantly, never repeats itself no matter how large the area it is made to cover, and keeps the eye moving while retaining coherence.

Unlike a movement, a style in the strong sense of the word (one that incontestably defines a whole era) is born gradually and anonymously or not at all. It can’t be wished into existence. Passionate workers tending to their plots are the only people who have the power to help new styles into the world.

The history of architectural styles can be explained by reference to the history of mathematics, which is not without a beauty of its own. You don’t have to be good at mathematics to appreciate it, because it very often is distilled in simple, powerful ideas. A Greek temple expresses the classical conception of space. A cathedral is a triumph of tectonics, achieved through trial and error. The Baroque could only splurge on complicated curvilinear configurations because it had a method for calculating them with confidence.

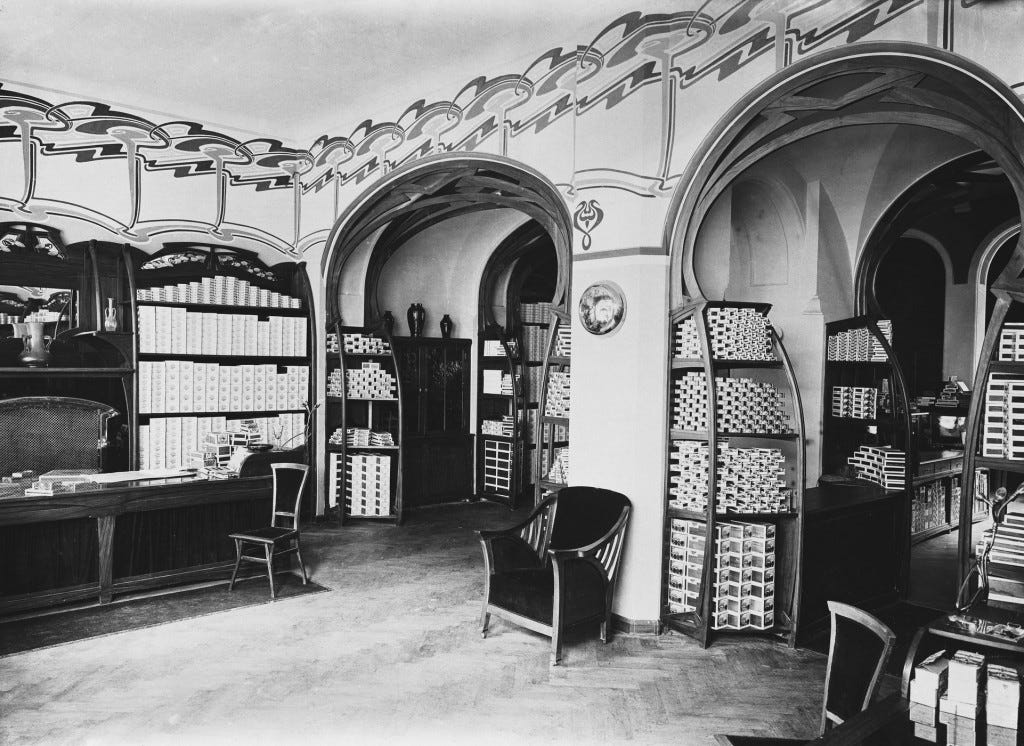

Even Art Nouveau, which could be called a style only improperly in this context (it was more of a harbinger of biomorphic and biomimetic design concerns), owes much of its appeal to mathematics. This beloved aesthetic is rich in subtle tensions held in equilibrium within networks of lines.

Belgian architect and theorist Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) laid down the unspoken principles of Art Nouveau as follows:

“A line is a force which, like all elemental forces, is active. Several lines that are connected but are working against each other, have the same effect as several elemental forces working against each other. This truth is decisive, it is the basis of the new ornamentation.”

An in The Renaissance in Modern Craft, he wrote: “The exceptional beauty proper to the works of engineers consists in the fact that this beauty knew itself, just like the beauty of gothic cathedrals had become self-conscious.”

***

If you could travel back in time and present a Baroque mathematician with 21st century digital design tools, they would have no problem grasping the basics, and they would get super excited about spline functions. The fact is, their way of thinking about space was not so different from ours, and they were accustomed to doing the same type of work we do with computers using only brains, pen and paper.

The Baroque fascinated Gilles Deleuze, the single most influential philosopher behind the aesthetics of parametricism (and the trends that followed it.) I promise this has nothing to do with fuzziness, chaos, or being a furry. Only people who have barely once skimmed Capitalism and Schizophrenia think that. I’m taking about another book, maybe his best: The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. In it, you can find weird but precise ontologies and exquisite digressions on music, and it all turns out to be about folding.

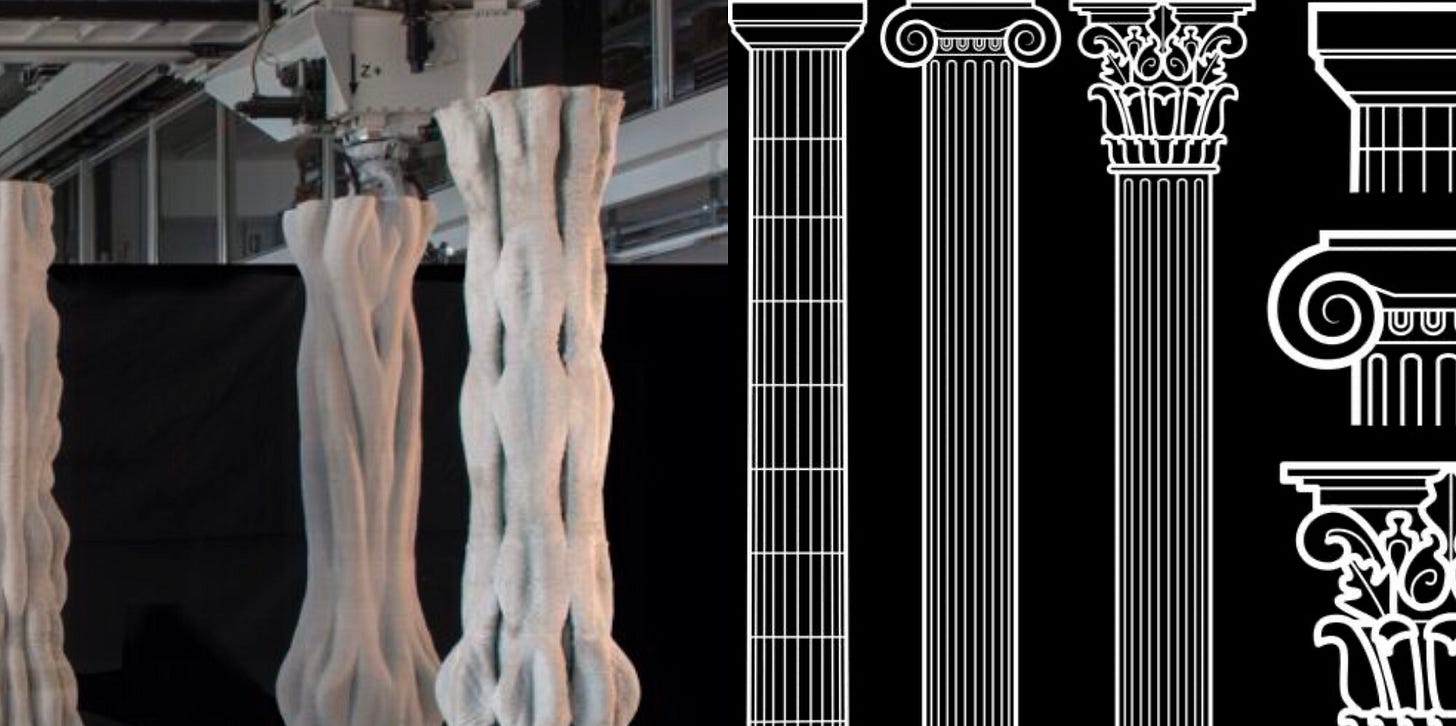

Deleuze’s concept of the fold was seized by designers eager to elevate things like NURBS, laser cutting and additive manufacturing into a new aesthetic sensibility. They weren't interested in epochal breaks but instead wanted to extend the logics of the 16th and 17th centuries into neobaroque futures.

French architect and writer Philibert de l'Orme (1514-1570) is one of their icons. He was highly original, but he knew what he was on about. His father was a master mason: stonecutting ran in the family. Philibert had been on the job from a young age, absorbing not just intuitive knowledge and timeless taste, but an entrepreneur’s eye for cutting costs by streamlining assembly. When the son came to design intricate vaults and trompe l'oeil cupolas, he devised modular solutions and coordinated systems where each component part is responsive to variations across every other part, just like in contemporary robotic fabrication.

Consider the following problem: how to make a squat cupola soar upwards in the eye of the beholder? By progressively reducing the size of the sunken panels as they approach the top, the eye is cheated into perceiving an illusion of vertical depth. So far, so good. But how should one break down the pattern into easily cut pieces? Solution: subdivide and distribute it around horizontal courses. Each course features only one block design, flipped upside down and repeated. You could probably build this marvel using a 3D printer, a CNC file, and assembly instructions. It would feel native.

Such is the art and science of cutting solids, or stereotomy. Stonemason and laser tinkerer participate in one and the same tradition. The stonemason visualised information through epures (stereotomical drawings), which could get as detailed as to include several variations for the same component. Not quite the range and instantaneous improvisational capacity we associate with a non-standard component, but close.

A question now presents itself. If the architecture, craft knowledge and engineering of past centuries, left free to follow their own course, would spontaneously have developed into something we could recognise as contemporary, why did modernism need to disrupt everything? My guess is that modernism’s iconoclastic reaction wasn't a rejection of the past as a whole, but of the recent past more specifically.

I remain unconvinced by historians of architecture who claim that postmodernism is a transhistorical phenomenon, already present in premodern and early modern times. This seems to imply that pre- and post- are natural allies against the Modern. From prehistory up to the 19th century, all eras are rallied under the same banner.

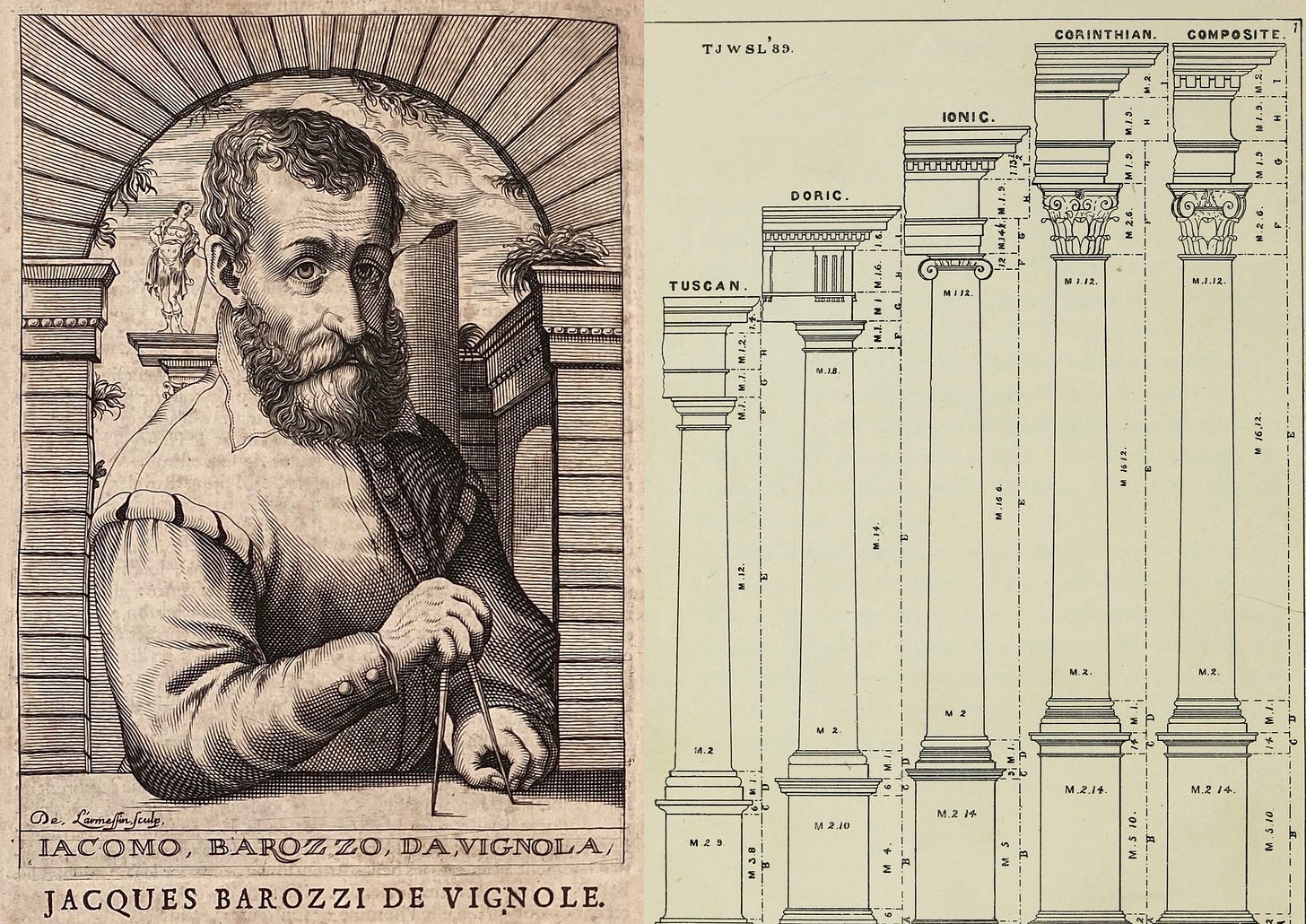

In one such account, the Five Orders by Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola (1507-1573) is read as an early postmodernist gesture. Vignola’s laying out of disembodied elements of Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite orders, combined with the relatively vast reach of a printed book at that time, is interpreted as an invitation to pastiche and quotation.

The trouble with this theory is that 16th century architecture didn’t think of itself as a distinctive and wilful “style.” In the minds of Renaissance and Baroque people, there existed knowable truths concerning architecture, and these truths were alive: they could be improved, reformulated, and added to. Classical aesthetic codes were a universal heritage, open-source software. They weren't an ironic in-joke.

To a certain extent, this state of affairs was dependent upon Greece not counting for much as a country or a separate culture. (For Vasari, greek manner meant contemporary Byzantine style, whereas the manner of the ancients was simply correct, not least because it amalgamated the fruits of Etruscan and Roman genius into its canon.)

Then along came the 18th century craze for antiquarianism, Romanticism, and the 19th century fight for national independence. As Greece yielded up more and more of its archeological treasures, and German historians insisted on its ethnocultural specificity, Greek art embarked on a journey in European consciousness. It was being othered: it wasn’t the self-evident basis of our curriculum anymore; it was becoming just one of our many others, like Egypt, the Orient, or ancient Mexico.

One consequence was that our sense of style was sharpened. At the same time, ancient Greece became a revenant, available for shallow revivals but not for true renaissances. Invoking it ceased to come naturally as one’s birthright. As it slowly devolved into a mere automatism, it froze in time, ceased to be understood, and fell away from the living stream of architectural thought. When modernists attacked inauthentic decorations, they must have thought they were only there to dress up soulless buildings.

If something of the modernist project deserves to be salvaged, it's the capacity to rethink architecture from first principles. Just this capacity has survived unscathed and continues to inform the myriad currents of post-digital architecture. We have lost something: a unified vision that was at once applicable like second nature and hospitable to innovation. We have gained a matrix for generating abstract, highly intellectualised frameworks that ask much of the architect and of the public alike. The built world has exploded into a plurality, and the only homogenising forces are market forces, which become visible in the brief. But even as each micro stylistic gesture refracts every other like a fun house mirror, a reality to be mirrored endures: there are still people who need buildings to live in, fragile environments, and stubborn, wise materials. Maybe nothing has been lost.

***

Styles are for art historians and curators, not creators. They are afterthoughts. What really matters are artistic decisions, and in architecture these are taken not once and for all, but in layers. Between aesthetic layers come engineering layers, logistical layers, and so on.

The decision making unit today is neither the lone genius nor the school, but the practice or studio.

If you want your decisions to be memorable, you need to rethink architecture from first principles, and slowly make your way up and down the hierarchy of layers.

What are the primal architectural ideas that shape your world? This layer is phenomenological, concerned with perception and experience, so you can make aesthetic decisions now. Maybe you prefer keeping interior and exterior separate. If so, you’ll need an envelope (this could be a membrane or an enclosure) and openings. If you like porous structures, you’ll need screens and lattices. If nomadic space is your thing, you might want to arrange continuous transitions of light, temperature and material and plot semiotic routes across them.

Then you must satisfy the conditions you have set yourself by devising appropriate building elements. Answer again the question, what is a window? How do you like your floors? If you are a talented innovator, your formal solutions may be turned into codified elements like the open plan, the ribbon window or the column. Still, this layer is mainly governed by engineering considerations.

Next comes typology. A type is a building archetype that retains its spatial identity across time, persisting even as decoration, technique, material, and formal articulation evolve. Continuity of use often defines a type, but memory and the stories people tell about the buildings also play a role, so typology features a strong aesthetic element. A brutalist guard tower shares more in common with a castle tower than with a skyscraper. (Interestingly, even ostensibly open-ended revolutions like parametricism ultimately aspire to create their own fixed types. This became evident when architects used genetic algorithms, inspired by the theory of natural selection, to simulate families of buildings.)

Finally, if you are in astronomical demand, you can start thinking about imposing your taste at the urban scale. You could harmonise the skyline across multiple buildings, replace urban grids with delicate systems of gradients and thresholds, plan the city to surprise and soothe the distracted brain of a tourist or digital nomad, select urban furniture, and dictate landscaping.

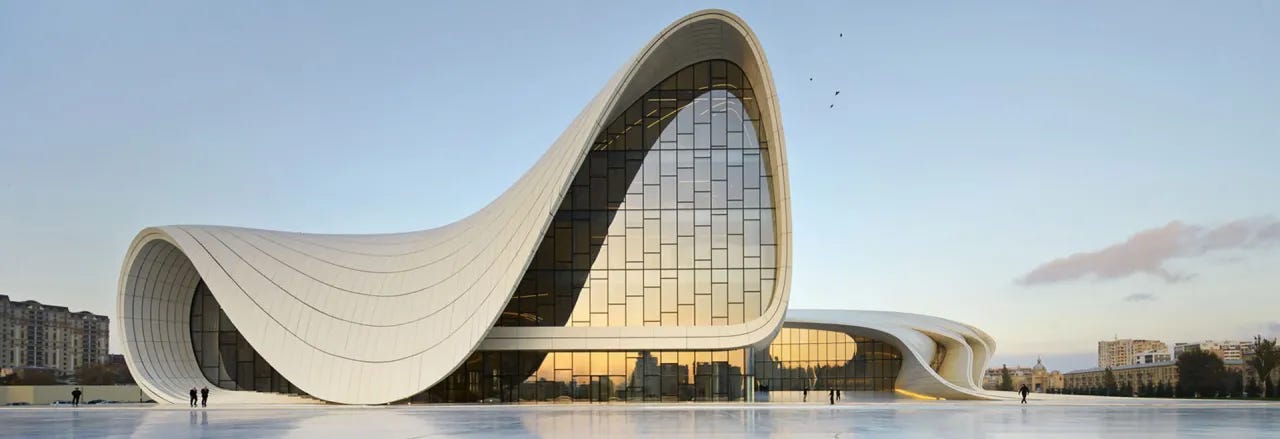

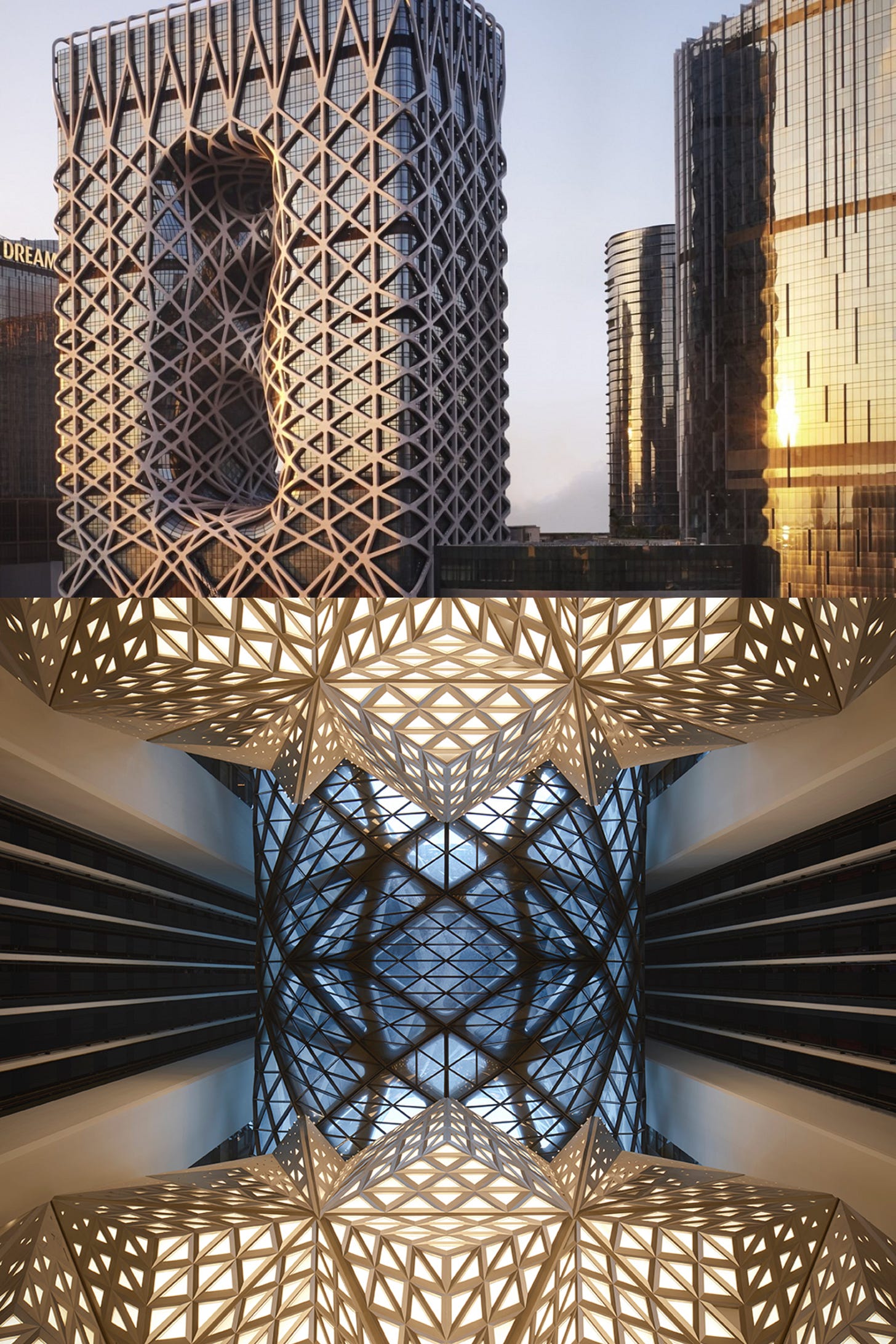

Zaha Hadid and her studio have done precisely this. At the start of her career, Zaha Hadid was supposed to be a deconstructivist, but in reality she was never anything other than herself. And yet she was no maverick: her designs look like something anyone could, in retrospect, have thought of. They have an impersonal feel (maybe projected backwards by the aura of success) except that their sheer quality tips you off.

She has done the work of rethinking architecture form first principles without erasing the imprint of the past. Instead of striving to reproduce a certain look for the eye of the camera, she has worked layer by hierarchical layer, adopting recognisable types from Mesopotamian history here, transforming calligraphic signs into facade elements there.

Zaha Hadid is the most successful and influential firm in the first quarter of the 21st century. Architecture doesn’t need a new style (or an old style). What it needs is Style with a capital S. After all, the only truly soulless building is the one that’s generic, unresponsive, carelessly imposed.