I downloaded my digital copy of Attila on April 1, 2025. It was release day for both Coll’s novel and Javier Serena’s fictionalized account of the writer’s life, also titled Attila.

As soon as I began to read, I suspected I’d fallen victim to an elaborate literary hoax. Here was a writer whose existence I had entirely overlooked until a few weeks earlier, “the last cursed poet of Spanish literature,” a recluse who had committed suicide upon completing his final, perplexing masterpiece, and was only now being translated into English. It all sounded too romantic to be true.

However, any lingering doubts stirred by the well-orchestrated Praise, Translator’s Note, and Prologue sections soon paled into insignificance. The novel was so astonishing I simply didn't care who had written it, how, or when.

The soul breathing through the pages seemed to confirm a few details. The author's personal legend casts him as an avant-gardist born too late (in 1948), a visionary married to a painter, a polymath more at ease in Europe’s past than its present. If I found the reading easier than translator Katie Whittemore forbiddingly predicted, it was probably because I share cultural references with the author.

That's not to discount the novel’s power. It is, without question, a deeply dangerous book. Half a page is all it takes to plunge the reader into a meditative state. You can sense the air shifting around you, your body shifting gears, your brain giving off a different kind of wave.

Most readers of Attila will likely skim entire paragraphs, listen for the music of nonsensical words, and cling to the semblance of a plot. But deep attention is as rewarding as it’s scary. I’d suggest arming yourself with reams of paper. Take notes, copy down sentences, draw maps of this mental wilderness, sketch the visions, try to figure out the topologies.

That’s exactly what I did, and why this Substack post exists. I had so many jottings on my hands I figured I might as well do something with them.

I’m not offering these as an authoritative interpretation of Attila (I’m sure many minds are already at work).

Think of this as a travelogue.

(In the following, Bold Italicized words are direct quotations.)

***

The surface of Attila is perturbed with History and Empire. Its elemental core swirls with the forces of Nature.

When the setting is a tottering Rome, it’s mostly safe to assume the book will concern itself with the reasons civilizations fall, what can be done to prevent this, what can't be done, and why such questions are wrongly posed. What could last longer than its own duration? Attila has all of this, in abundance.

But Aliocha Coll did not devote the last of his life and his sanity to a merely political theme. The collapse of civilization is only one facet of a deeper, more all-encompassing dilemma. There’s a Gilgameshian drive at work, a longing for Eden and immortality that reaches beyond the personal and the collective to address the very structure of reality.

… like an egg, which, having reached a state of perfection, should want to make itself perfectible, never new again …

The dilemma manifests itself in language. If the writer seems to battle against language, to want to tear it apart and dislocate it, this is less a literary experiment than a treatment of language itself as the symptom of a disease.

Woe to the drama if unexpected actors enter the stage, spontaneous maskless individuals and troupes with tongue. For someone will lose their point of view and will not spot hope at the bottom of Pandora’s box.

Attila seems to warn that cultural decline is a self-imposed ailment, inevitable only when we fall into the wrong perspective, the wrong relationship with Nature. It starts with the over-coding of reality, scientific determinism, and the tyranny of efficient causality. (In the novel, these are often symbolized by lineal descent or paternity.)

When the adventure of Life is mapped and predicted, from past to future, from simple to complex, from initial brutality to emerging intelligence (the life-cycle of virtual cellular automata), a culture is bound to apply those lessons to itself, anxiously looking for signs of decadence and airing out self-fulfilling prophecies of doom. Choosing to value Life over Mechanism doesn’t challenge the framework if one has already accepted the premise that life forms are only temporary impediments on the way to thermodynamic expenditure. As freedom is foreclosed and senescence foretold, Vitalism can only connive with determinism by casting all its hopes on ever-diminishing “untapped” resources, overvaluing opaqueness, violence and cruelty as manifestations of cultural youth.

“Poor things, increasingly caused … poor cause, each thing increasingly vicarious … and decreasingly vicissitudinous … poor occasion, each cause plurally fantastic, and its thing singularly immaterial.”

Life and Nature, however, can and should be understood in more than one way. We are symbolic creatures, we can’t stop trying to impose a code on reality, and there is something necessary and justified about codes. At the same time, reality defies our totalizing grasp. Science discovers parallel universes, black holes and dark matter. Nature insists on presenting a double aspect to us, on twisting time so that the end pulls the origin. (In the novel, this is symbolized by non-reactionary backward movements, or non-patriarchal “atavisms” that open onto the future.)

The double vision doesn’t see the tree of winter shrinking earthward, nor from the sky … it sees it gathering, ovoid, on the horizon, the other horizon.

***

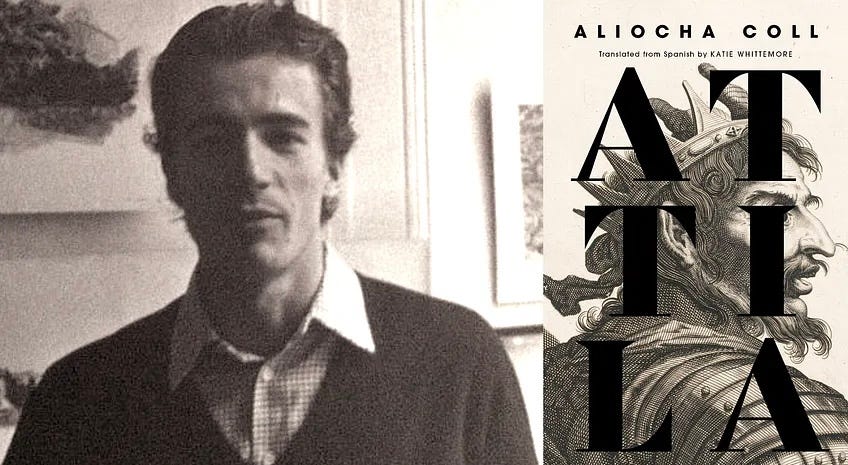

For lack of better terms, I’ve organized Attila’s recurring concepts under the headings of “digital” and “analogue.”

Language, heredity, binary logic, determinism, causality, linear time, daylight, history, reversibility, symbolic systems: “digital” ways of apprehending the world.

The continuous, the inarticulable, the sensuous, the morphing, night (which continues to exist, hidden by the sun), sons, eggs, the suprarational, the outside of history, recursion: “analogue” ways of knowing.

For me, personally, the main message is that Nature, at all scales, responds to both forms of perception, but one of them is clearly in danger of becoming forgotten.

How much it must have cost the rock its hardness, and the water its descent. How much it must have cost the tree its pivot, and the wind its coiled spiral. How much their bodies must have cost the laws of mechanics, how much strength must have cost the strong, and inertia the inert. So much effort, and such a chore. How axilly the thing goes about unfolding, threatened, always, by reduction, by the script of its identity.

***

“Analogue” has two meanings: technical and poetical. This is likely no coincidence.

relating to or using signals or information represented by a continuously variable physical quantity such as spatial position, voltage, etc.

a person or thing seen as comparable to another.

The analogue / analog is not an imperfect, superannuated form of technology. It is a constant possibility. “Real” computation, which is only theoretical, is analog: it uses infinite-precision real numbers. In the last decade, the idea of wave physics as analog recurrent neural networks (RNNs) has been floating around as a proposed source of fast, cheap and sustainable computation. This would harness the natural motion of light, sound or other waves: the veritable rhythms of the universe.

Attila seems dictated under the spell of elemental rhythms. By keeping the idea of the analog (and poetic analogy) in mind, I was able to read these rhythms as something more than expressions of a naive cosmic vitalism or of the more vulgar strains of Lebensphilosophie.

***

Chapter I, Laocoön, sets the tone for Attila and his son Quixote’s relationship by thematizing another kind of fatherhood, one that loves “distant sons” and puts its trust in them, as [his] sons’ youth may exgender [him]. [He] can congender [him]self in it.

Laocoön is a mythic father who hopes against hope for his sons’ survival. If he succeeded in saving their lives, he’d be releasing them into the unknown, since the world they’ve known is hurtling towards destruction. He’d also be unable to mentor them.

He’s not a patriarchal figure. His story is slightly subversive. He has no control over his legacy, his role is sacrificial and his love of futurity is absolute. The Laocoön Group at the Vatican Museums says it all: helpless tenacity in the face of vulnerability, Life’s last word perpetually echoing in stone, fleetingness eternalized.

A father should protect his offspring. Barring that, Laoöcon does the next best thing: he leads by example, greeting their common demise with a resounding “no”. Death does not have his consent.

If a Christian sculptor had created the group, we would be justified in feeling awe and compassion. While no stranger to pity (ancient funerary inscriptions urge the traveler to take pity on the dead, especially if their end was premature), the pagan artist likely saw, like Aliocha Coll, something heroic and inspirational in Laocoön’s agitation.

“Exgender” seems to be an inversion of “engender”. It could refer to another kind of causality, where the distant future influences and vivifies the past.

Instead of a patriarch whose epic stature and achievements, flush with newness and unspent energy, are on track for erosion and eventual meanness in his descendants, we see a primal father who contains all possibilities and conspires with all times.

Since the group’s survival is at best uncertain, however, it does not ultimately seem a question of temporal descent in one direction or another. “Congender” signals a kind of simultaneity in Life’s operations, marked by mutuality and indifference to the bare calculus of survival.

Interestingly, “Attila” means “little father.”

***

Chapter II and the pages leading up to it lay down the conventional narrative of collapse: young barbarous peoples inevitably displace an exhausted, overintellectualized civilization. This is a thesis the rest of the book strives to complicate and confute, but for now, the author brazenly impersonates “the Hun”: we read that nothing sprouts without weapons, in every man there is a viper and a wise monkey with a mirror (body and mind are at odds, in precarious equilibrium), the sword is the greatest premise of reason.

The Hun is a centaur, defined by the landscape. The horizon distinguishes all quadrupeds. He’s free like an untamed wilderness, earthy and volcanic, but he feels a violence bubbling in himself, whose predictable outlet is dominion. The rider hung from the axle of the landscape … with the axle of the landscape in the hand of an extended right arm.

The Hun could incur Rome’s fate by giving free rein to his lust for corralling the “georgic” hills. That's what Attila plans to prevent. The slope, on its knees, became border … Feral trees preferred ravines to roads.

The son and husband of painters, Aliocha Coll probably absorbed a painterly way of seeing and thinking early in life. His prose is a canvas crisscrossed by impossible perspectives, blooming colors, structural light. Almost plotless, the narrative moves like a series of allegorical paintings, distorted but never arbitrary: meaning arises from composition, from the vibration between figure and background.

In this painterly metaphysics, straight lines and linear perspective are instruments of violence, perpetrated on small forests ravaged by light and perspective, by civilization wielding agricultural implements: sickles point up against the wind, cutting the wind in a straight line.

Now language begins to mimic Nature. It behaves like an analogue medium, recording playful details that exceed any explanatory usefulness. Clouds and mountains play leapfrog. The cascade skips rope with the bridge. Nature overflows digital mirroring and appears in a state of double transmission. Nearer hyperbole, the earth is metric. Beyond hyperbole, the earth is a canopy of formless profiles.

In the sky, a translucent egg contains a man and two twin men, lantern of itself. It's a recursive life unit, self-embryonizing host of potentiality, undetermined but also somehow fully grown. A pageant of symbols next crowds the sky with flags, coins, registers, relics, propaganda, measuring devices, clocks, ghosts. The sky is completely “digitalized”, flattened into representation.

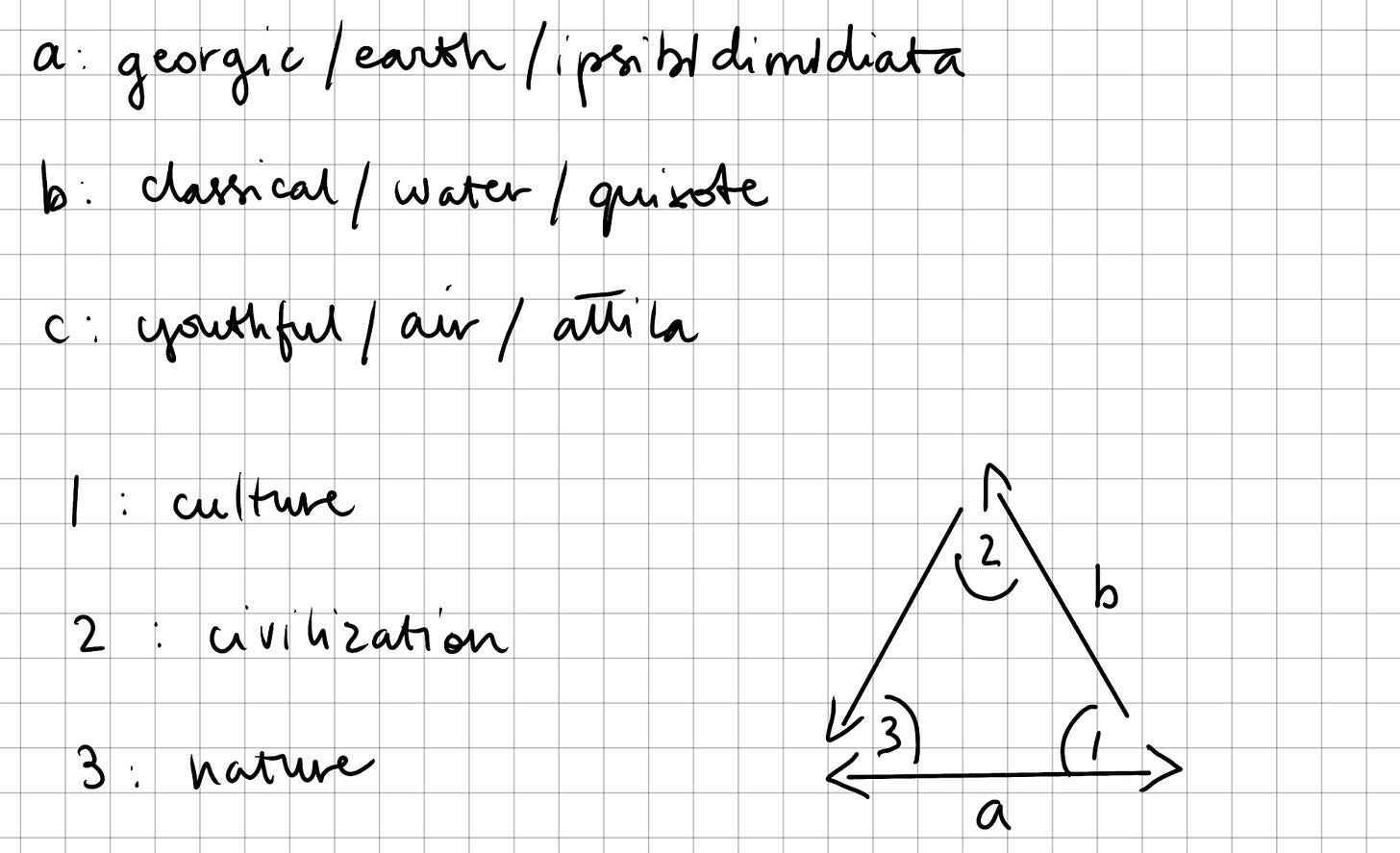

The name Ipsibidimidiata makes its first entrance here. We later learn that she is Rome’s daughter (“Rome” is the Emperor's ceremonial name), Quixote’s fiancée, and much else besides. I take her name to mean “self split in half down the middle,” “half of herself,” “double the half,” or “she whose profile is twice repeated.” She is teasingly introduced by this question, more poetic and precise than any of my clumsy etymologies: What shall I call you, half that never begets symmetry, but always homothety? Half alone only, and half alone accompanied by your homothety.

***

Chapter III, The Hun and the other, explains Attila’s and Quixote’s projects for overcoming the end of Rome.

Quixote has internalized the iron law of civilizational decline, and wants to bolster Rome’s inheritance with newer, ascendant forces: those of his people. By mixing with Rome and defending its territory, he would have the Hun embark on a civilizing course, accepting cultural mortality as the cost. Rome’s heir will meet Rome’s fate in the distant future. But to Quixote, this is better than a nomadic existence, and better than abandoning Rome to the cruel mercy of the Vandals. In the interests of Rome, Quixote wants the Hun to invade first.

The huns have been telling the same story since Quixote was little: “how we had come to save it, how our culture had put right that decadent civilization, how our natural law had healed its civil law in the midst of total corruption, how our cosmic poetry had dissected its chronic mannerisms … and then, then we returned to our origins, to that free and immediate projection of the sky onto the earth …” But no matter how monotonous or obsessive these claims, differing interpretations are still possible, and father and son find disagreement.

Between them, Ipsibidimidiata briefly shimmers like a third, ignored possibility. She composes wondrous poetry, knows rhetoric, and meets Quixote’s lucubrations with sibylline protests, like: “But all that is origin is not end, and everything that is end is not origin.” Her understanding of time contradicts the idea that an irreversible course is predetermined: rather, a known outcome is abstractly reversible, and so doomed to repetition, while freedom is recursive.

Reversibility is digital in spirit. Sirocco-scraped grains of sand ran like the organs of irreversible hourglasses (analog clocks) bearing witness to completely random time.

Having summoned Quixote, Attila proceeds to expound his plan for an apolitical civilization in the steppe, that is, a natural civilization and a classical culture, without cities. To further his plan, he’s sent hostages to be brought up in Rome, including his son. Recalling all the hostages will enable him to instruct his people in all that is best in the Roman heritage. He distrusts monetary economics, the radial administration of the law, he would speculate in philosophy without speculating in trade, and enjoy the leisure of poetry without the business of slavery. He’s not a barbarian, but, satisfied with having dared to imagine an alternative pattern for history, he’s prepared to abandon Rome to the barbarians, to what is brewing in Europe, the eternal opposition of a classical civilization and a natural culture, which is always solved by replacement, for the sole and greatest increase in oppression. Attila doesn’t seem to believe this course is necessary in Nature, just that peoples have so far failed to build and grow in accordance with Nature, which he identifies as humanity’s savior. “We are going to save this world … but not to save the salvageable but save the savior.”

Quixote rejoins Ipsibidimidiata. They exchange news, discuss literature and philosophy. Their love, however, is founded in perception, something that can’t be flaunted or acquired by dubious means. Separated by their embodied vantage points, they nevertheless experience similar epiphanies and oscillating, nearly synchronized perceptions, completing each other, almost but not quite coinciding.

Together, they follow their own ethics of perception. An image wanted to be born, attaching to a cracked mirror … no, wanting to detach a whole mirror from a cracked image.

Since Rome wants Quixote to stay, and Attila requires his presence, the lovers decide to strike out on their own, trade history for their love story, and embark on a journey, in quest of a third destination.

Weary from their travels, like adventurers in a medieval prose romance they seek shelter in a cave, only to realize they have entered a space of allegories and wonders.

Quixote and Ipsibidimidiata looked at each other slowly in the cave’s ground-skimming glow. First Quixote saw Ipsibidimidiata’s profile, but then, as they turned toward one another, instead of seeing a different cohesive profile, he saw, on the other side of her face, the same cohesive profile as the first. Ipsibidimidiata saw Quixote twice, not doubled, but successively, not continually but with infinitesimal discontinuity, as if between Quixote’s vision through one of his eyes and the vision through the other, some tooth had been skipped in the cogwheel designating his position. Both were overcome by the same spell in which there appeared one single dream.

He appears broken and mechanical. He’s a digitalized man, fragmented by inherited codes he has imperfectly rejected. She’s the analogue woman.

Think of the apparition they encountered earlier in the cave: a man with an excess of identity, clinging to a woman's lack. Just as with Laocoön, the secondary characters, drawn form Biblical stories and Greek mythology, are like personages in a masque, emblems of the main trio of father, son and daughter, re-enactors of their dilemmas.

The next chapter, for instance, has Solomon trying to solve the problem of rejuvenation by splitting and splicing the live and dead sons of culture and civilization. Of course, this crude plan of action will produce monsters.

***

Chapter IV, The Huns and the others, opens with a quantum allegory. A rider carrying Attila’s message to the lovers reaches a fork in the road and takes both paths: down one of them the dust followed behind, and down the other, ahead, alone. The dust isn't bound to a binary choice. Two messages arrive to divergent identities of Attila’s son: a coherent script to Hydattila (Quixote’s self-chosen alternate name), and a string of random letters to Quixote. In light of Quixote's rebellious use of grammar, this reads like the fulfillment of a wish: an excessive communication that recognizes the unspeakable freedom of the analogue self.

Quixote rejects inheritance and paternal authority through language and naming. He doesn’t know that the father is freer than the son.

Following this impossible bifurcation, we see one instantiation of the lovers take an alternate route to freedom, not by sea but through a forest. Here, they meet their doubles. Notably, Quixote’s double is named Hydattila, but Ipsibidimidiata's double is still named Ipsibidimidiata. Not polar opposition, but reverberating multiplication.

All four were contemplating, admiring, Ipsibidimidiata’s other profile, the conceived and uncreated: perfect, pluperfectly symmetrical, which they knew and remembered: for there it was missing: there: beside the other: missing.

Ipsibidimidiata's missing profile is a template of beauty preceding her origin and as yet unrealized. It collapses the origin and the end. It can only be approximated by beauty multiplying itself in non-identical repetition: this is the vindication of creaturely mutability. As Ipsibidimidiata says, beauty is perfected through doubling, which is not duplicitous, unstable or incoherent, but richly alive.

The forest where these revelations take place is a direct heir of European prose romance’s gardens, isles, and enchantress's bowers. These are textual environments that serve to verify philosophical hypotheses on the nature of Nature.

Usually, an enchantress seeks, though symbol-saturated, theatrical artifice, to have the best of both worlds: eternity and time. She traps knights in unchanging bliss, alienating them from the rhythms of life and from deeper wisdom. The enchantress or fairy (a personification of Nature’s counterfeit) is introduced only to be dethroned by true Nature.

This genre seamlessly connects with a type of text that has Nature herself deliver an oration, in which she defends her adherence to God’s plan and reveals her counterintuitive pact with eternity.

In romance, the forest often tests virtue. Here, it tests perception. It asks: can you see in two ways at once? Can you dream and also behold?

Beauty can double understanding rather than resolve it. It's Nature insisting on being known in more than one way. The analogue is not merely pre-digital or anti-symbolic, but an infinite supplement of perception.

***

Chapter V, No one or no one else, opens with a long, cryptic poem said to have been inspired by a “Ligurian quarry,” which seems to be an allegory for anti-natural technological exploitation. Crypts of the vitibund, impermeable to the soul.

It makes all the more sense when the rest of this chapter is devoted to disturbing historical developments, overlaid with visions of the coming technological hell of WWII (followed by Nature’s polymorphous, hallucinatory revenge.)

Among the mocking, monstrous growths of the earth, extraordinary flashes of insight: each element found complexity in its minutiae and no simplicity in its subtle peers. This is a direct attack on the theory of emergence and its cybernetic licensure. Complexity is not an emerging phenomenon, but the ground of being. The part is greater than the whole: it contains infinities.

Cybernetic simulations do just that: they simulate, they don’t explain. Their vaunted recursion is applied to arbitrarily delimited components of a system, and cumulated errors in delimiting lead them away from reality.

If “minutiae” can’t be computed, compressed, or exhaustively described, then even decreasing optionality in the aggregate can't absolutely rule out novelty and surprise. These need not arrive from without, in the form of external “contingency”: they are already present in the innermost core.

Nature is free: the trunk decided that this year it would not make firewood of its sapwood leaving empty a ring of its onyx age … the sylvan root did not consent to that urbanity of bonds and darts and whips precisely because it had a vision, not only of founding, but of the main foundation.

***

Chapter VI, Untimely Temporals, sees Ipsibidimidiata transported to a strange location, where Attila declares that he’s chosen her as his historical daughter and his utopic daughter.

They are more alike than relatives, because unlike Quixote, they are prepared to live beyond history, in a never ending stream of anecdotal memories. Attila is not interested in warring to preserve art. He believes the opposite to be the case: poetry preserves history artistically. Ipsibidimidiata believes in the saving power of love and beauty.

All the mythic personages reappear in this chapter, and start debating the usual questions. “Distrust a gift of correct answers that can only hit upon errors.” In the quick give and take, the novel descends into deeper obscurity as it doubles symbols, fragments referents, and disarranges perception. It's not trying to be obscure for obscurity’s sake. It disorients in order to reorient.

It’s all part of the central quest, which is not artistic or political, but ontological. The point is not to decide on either rescuing or surrendering civilization, but to rejuvenate perception.

“With a turned back, the cherub guards the exit from Eden” not to block access, but because we have stopped seeing properly. We face permanently away from it, we have become estranged from how to perceive it. Eden is not forbidden so much as incomprehensible. Or unnoticeable. “The fruits of the tree of life make no noise when they fall,” one of them thinks.

Of course, it’s a poetic, not a religious Eden. Like the many strange angels that flit through this book. The angel of the folds, stranger to the summary … uncuttable pineapple, untotalizable bunch … tangled membrane. The counterfoil of the orb ... All of Nature is the angel’s great wing.

***

Chapter VII, Double by day and hun by night, chronicles Quixote's dreamlike journey eastward. Every decline is a pilgrim / If with courage it cradles its debris. China is the fly in the ointment of the Declinist hypothesis. It's weathered many historical storms, and continues meeting new challenges with undeniable protagonism. China’s entry into modernity forced it to adopt Western technology, but it still shows glimpses of an idiosyncratic way of doing things. It’s also home to legendary Immortals who played chess atop high mountains. Quixote came to China in hopes of wresting from it the secret of its “eternal” youth.

He’s soon distracted by the urbanizing plurality of woman. In other words, he goes through a period of errancy, closely resembling the romance arc of the “false beloved.” The knight encounters deceptive images which test his desire, discernment, and fidelity. The false women are not simply foils to the true one: they are distorted expression of the beloved, private fantasies which he must renounce and deny in order that his love conform to reality.

Quixote sees Ipsibidimidiata’s profile superimposed on these women, who are wounded, marginalized and grotesque. Her image is refracted, analogically dispersed through a broken world, always from the side, never whole, like a coin or a silhouette. He doesn’t desire the women themselves, but what they reveal in fragments: Ipsibidimidiata as recurrence, as partial infinity repeating across actual occasions. Quixote is trying to locate a timeless, incorruptible principle in the world of flux and decay.

His search leads him to an enigmatic elemental garden haunted by a personification of the feminine. Exposing his selfishness and hypocrisy, she rebukes him for circling “like tigers around all that grows, while you ambush the cities, inhabiting them illegally wilded, to prey more treacherously, under that color, upon the pretexted ruins.”

Women, she informs him, have the “deposit of the original answer, moreover, the deposit of the original alternative.” “To live or to die.” “No. To live or be born.”

***

Chapter VIII, Lullaby sans bemols, ties everything together. We’re now outside of history, in panoramic limbo, and after the perceptual revolution has been accomplished, “we hear the dance of eggs in every soul.” The offense that translated Nature into an impoverished medium is remedied. At least, it is for Attila and his wife Thalia, who have shed linear inheritance, proclaim themselves born from their adoptive children, free before their kin, taunt death and draw life from the hidden rhythm of creation itself, touching at every moment both the archaic beginning and the end, spring and evening simultaneously.

A retinue of masks blesses and admonishes their children.

Laocoön: “Where the worship of ancestors does not require art … there you will find Ipsibidimidiata composing the nonreferential … until you two compose the enigma that has no representation … the relative fold of all forms, through which the oldest thing is but an embryo … there you find that the date has no deadline.”

Solomon: “… your senses are like dried beans in the roomy pod of your consciousness … You continue ignoring that there is so much light with no radius, light with no focus, in your past.”

But the son is still internally divided.

As Quixote, he’s learned the feminine’s lesson, and he’s finally come to understand Attila and Ipsibidimidiata’s project: he, too, would wish to live after history and love after melancholy, practicing constant renewal for the sake of his future progeny.

As Hydattila (and still more as Absalom) he’s pulled towards abstraction. He has no faith in the future of art, and he finds a life bequeathed to anecdote but lost to history pointless and unbearable. A comparison with the author is inevitable (if a touch naive and possibly incorrect), mainly because pain enters into the equation. Aliocha Coll penned at least one (lucid and academic) text on pain, still unavailable to the general public. He must have had reason to think about pain so intensely. He desired suicide, if only to cease enduring, to put an end to the pain, if only to not to animalize, not to vegetate.

Ipsibidimidiata now vibrates in unison with both halves of her lover, and her consciousness becomes divided: she, too, feels pain, and sees that sacrificing life’s perfectibility to the perfection of art (the “ruin,” or all whose essence has been expressed once and for all) is also one of life's possibilities. They will have loved. Remember the ruin of the lovers.

One suspects that Laocoön’s plea to Quixote will be useless. “Don’t go back if your idea of the beginning is that of a progressive ingress and not that of an ingredient in the congress of the rhythms. Don’t go back if your idea of art is that of making the city a garden and not that of including the order of the day in Nature. Don’t go back, if your idea of woman is not the reform of her repetition that recaps her quantity.”

Aliocha Coll was unable to take his own advice. He took his own life instead. Maybe, he forgot that every dilemma is an incomplete reading. Maybe he didn’t forget, but he simply had no strength left. He left us the means to complete the reading where he failed. That task starts with reading Attila. And reading it again.

***

If Quixote chooses a tragic exit, what happens to Ipsibidimidiata after all this? I believe her story is not over.

Which got me thinking about Chinese-French artist Lysiane Luong, Aliocha Coll’s great love. What happened to her?

To the male reader I say, brace yourself. To wrap up all the cerebral stuff that went before, you’re in for a bit of female “autism” (gossip).

Online, I found works by one Lysiane Luong, Paris-born, 1951. They kept pointing to the “Red Grooms and Lysiane Luong Private Collection”, so I investigated that.

After breaking up with Aliocha Coll, Lysiane met American artist Red Grooms in 1986 (5 years before Aliocha’s suicide). RG had divorced his first wife, another woman painter, 10 years earlier, in 1976. Mimi Gross. They’d been married for 13 years. She was also a costume and set designer, and to judge by his later works, I suspect Red Grooms stole some of her ideas.

Somewhere between 1986 and 1998, Lysiane and RG were married.

They created Tut’s Fever Movie Palace together for the Museum of the Moving Image. It’s a huge art installation that takes the form of a movie theatre. It pays homage to classic Hollywood cinema in a childishly gothic way, channeling a blend of nostalgic wonder and eerie darkness that would have delighted Ray Bradbury.

Working on this project, did Lysiane remember Aliocha? Did she recall him debating with her, like Quixote with Ipsibidimidiata, the respective merits of lost civilizations, trying to decide if Egyptian art is more “animalizing” or abstractly rational? I’m just imagining these things. Lysiane is very private. I don’t know anything about her. I only know that she found a way forward.